Fascinated by the 1960s Space Race? Read our brief history to find out more

Peter Foy charts the history of the highly political race to put a man on the moon

By Peter Foy

Urgh. I know I’m going to say it, even before I’ve started writing. I can’t help myself. So let’s get it out of the way right now.

Space. The final frontier.

| Whoever won the race to put a man on the moon would surely establish their dominance as a global super power. |

There. Done it. And I’m sorry, but it’s true. Or at least it was true in the late 1950s and 1960s, when the US and Russia saw their space programmes as a key Cold War battleground. Whoever won the race to put a man on the moon would surely establish their dominance as a global super power.

The result was an exciting and pioneering period in scientific history. It really did feel as if frontiers were being broken. And if, like me, you were a young kid staring in wide-eyed wonder at the world, it was pretty much the most scintillating subject imaginable.

All of which explains why I’m keen to mark the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. So come with me on a journey through time, as I chart the events that led to that historic moment.

1957. Prior to 1957 human beings had already explored the solar system and many galaxies beyond, but only in the minds of science fiction writers like Jules Verne and H G Wells, or through telescopes. On 4 October, though, the first man-made satellite was put into orbit around planet Earth.

1957. Prior to 1957 human beings had already explored the solar system and many galaxies beyond, but only in the minds of science fiction writers like Jules Verne and H G Wells, or through telescopes. On 4 October, though, the first man-made satellite was put into orbit around planet Earth.

Measuring just 58cm in diameter and carrying a radio transmitter, Sputnik 1 was a prototype. A trial run for something much bigger. Just over a month later the USSR launched Sputnik 2. Six times the size of its predecessor, it carried more equipment and a dog named Laika: the first living thing to visit space. And, sadly, the first to die there.

The Cold War was, if you’ll pardon the pun, warming up and there was great consternation in the West about what the Soviets were up to. This political climate shaped the Space Race, as it did so many aspects of society in the 1960s.

1961. On 12 April the USSR launched another spacecraft, Vostok 1. This time the passenger was not a dog but a man. Yuri Gagarin spent 108 minutes in space and orbited Earth once before returning. To do this, he had to parachute from his craft when it was 7km above Earth’s surface. The Soviet scientists had not developed a way to land the craft safely, but the authorities were keen to press on with the mission regardless. They wanted to chalk up another first over the US.

1961. On 12 April the USSR launched another spacecraft, Vostok 1. This time the passenger was not a dog but a man. Yuri Gagarin spent 108 minutes in space and orbited Earth once before returning. To do this, he had to parachute from his craft when it was 7km above Earth’s surface. The Soviet scientists had not developed a way to land the craft safely, but the authorities were keen to press on with the mission regardless. They wanted to chalk up another first over the US.

Gagarin became the pin-up boy of the USSR and was feted around the world. He died in 1968 in an unexplained plane crash, giving birth to the theory that he was eliminated because he had become too popular.

Not to be outdone, US president J F Kennedy told congress in May that an American would visit the moon and return safely before the end of the decade. Again, the wider political atmosphere undoubtedly drove the announcement. But the race to land on the moon was very much on.

1965. On 18 March the Soviets scored another win when Alexei Leonov became the first man to leave a space ship and float in space. It was the first ever spacewalk and was greeted with unconfined delight by the politburo (the executive committee of the Russian Communist Party) and the Soviet propaganda machine.

However, the mission was not as successful as the publicists made out, for at least two reasons.

First, on leaving the pressurised atmosphere of the capsule, Leonov’s spacesuit inflated, making him too large to re-enter the ship. His only course of action was to bleed oxygen from the suit to deflate it, which put his life at considerable risk.

Second, on re-entry to Earth’s atmosphere the ship came in at the wrong angle and very nearly burnt up. It eventually landed in a snowfield some 900km from the target landing zone!

A scary experience for Leonov, no doubt. But at least his mission had a happier ending than poor old Laika’s.

1967. At the start of the year the US was clearly in pole position to win the race to the moon. NASA needed to prove the space worthiness of the launch vehicle and command module that would carry its elite astronauts skywards. A test launch, later to be designated Apollo 1, was scheduled for 21 February. During a rehearsal three weeks before the launch, tragedy struck. A fire, caused by an electrical fault, broke out in the cabin’s pure oxygen atmosphere killing all three astronauts on board.

1967. At the start of the year the US was clearly in pole position to win the race to the moon. NASA needed to prove the space worthiness of the launch vehicle and command module that would carry its elite astronauts skywards. A test launch, later to be designated Apollo 1, was scheduled for 21 February. During a rehearsal three weeks before the launch, tragedy struck. A fire, caused by an electrical fault, broke out in the cabin’s pure oxygen atmosphere killing all three astronauts on board.

NASA suspended all manned flights while the accident was investigated. More significantly, there was a huge political backlash and the future of the programme was in doubt for some months.

1968. By October the US’s space programme was set to resume. First, Apollo 7 spent 11 days orbiting Earth. Then, on 21 December, Apollo 8 launched. It was the first manned mission to the moon, timed to maximise TV exposure over the Christmas period. The mission achieved several firsts.

The first people to see the entire Earth. The first to see the far side of the moon. The first to witness “Earthrise” as they came from behind the moon. It was the first manned space ship to escape the gravity of one celestial body and be captured by another, and they did it twice.

NASA had proved that it could send men to the moon and bring them back in one piece.

| Apollo 11 launched from Cape Canaveral and four days later Neil Armstrong took “one giant leap for mankind.” |

1969. On 3 July the Soviet N1-L3 rocket was launched with the intention of orbiting the moon and photographing possible landing sites, but the launch was a disaster. This effectively ended the Russians’ involvement in the race to the moon, clearing the way for the US to establish its dominance.

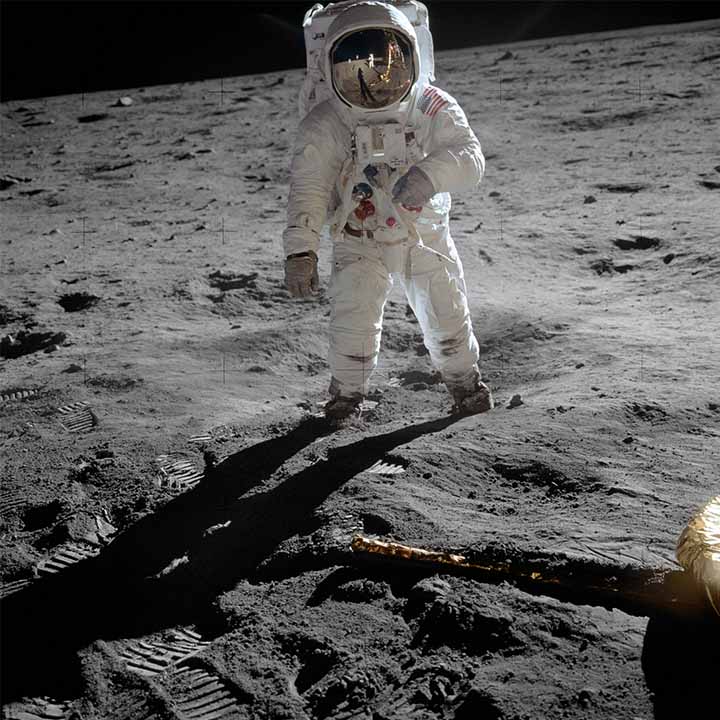

On 16 July, the country did just that. Apollo 11 launched from Cape Canaveral and four days later Neil Armstrong took “one giant leap for mankind.” Just a little over eight years after JFK committed the US to send men to the moon, the dream was realised.

The programme may have been driven more by nationalism and politics than science, and it undoubtedly cost an enormous amount of money. But it is probably humanity’s greatest technical achievement, so far. And even as a 60-year-old man, I still feel every bit as inspired by it as I did at the age of 10, watching the otherworldly figures of Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin bounce across the grey screen of a 1960s TV set.

Happy anniversary, moon landing. And here’s to the next 50 years of exploration and adventure. May the force be with you (sorry!).

Published: 9 July 2019

© 2019 Just Recruitment Group Ltd

If you enjoyed this article, you may like – If men are from Mars and women from Venus, who has furthest to travel home?

You may also enjoy – Weather myths: fact or fiction?