Why I became a writer: a builder’s tale

After 40 years in the trade, Ipswich-born builder Paul Allen decided to retrain as a writer. Here’s his story, in his own words

By Paul Allen

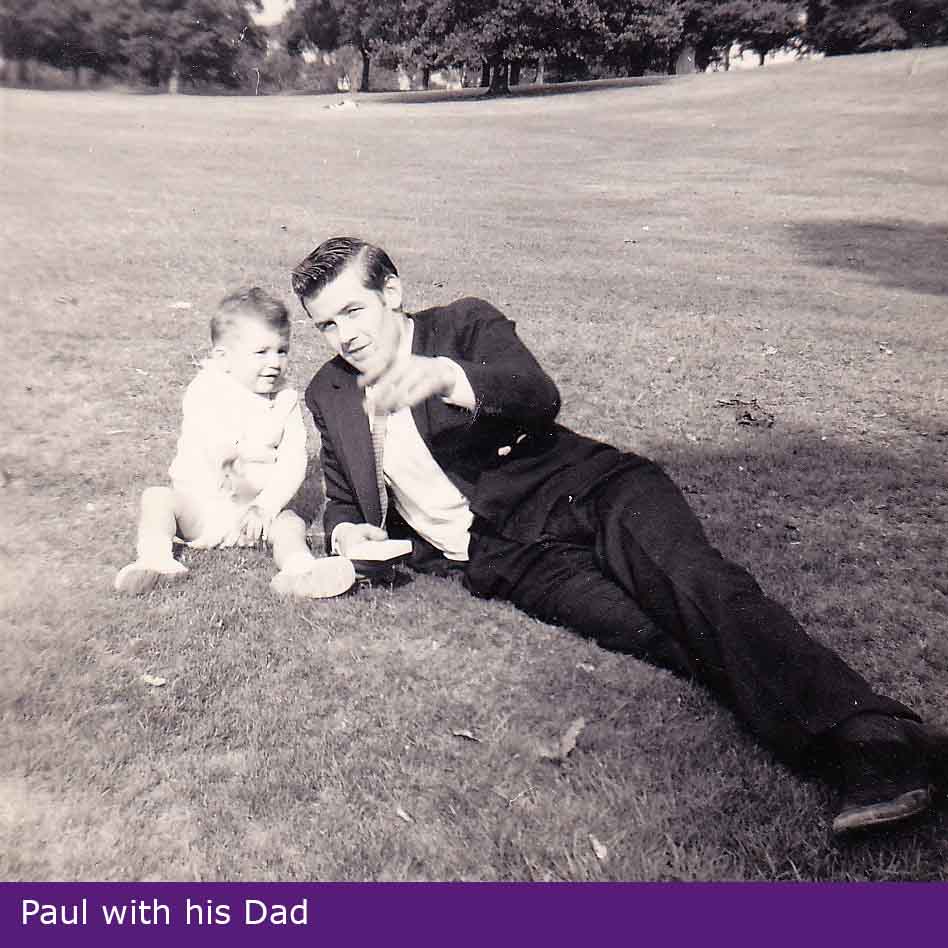

I left school in 1975 at the age 15, to be a bricklayer with my dad. I stayed on the trowel from then on right up to the present day. And yet, I’ve just completed a three-year full-time BA (Hons) degree in Creative and Professional Writing.

| When I was 12 years old, I saw my dad cry for the first and only time. When I asked him why, he told me something I didn’t understand. |

How did that happen? Or, more importantly, why?

Having just cleaned out the mixer for the day, I’ll put finger to keypad (quite literally – I can only type with the one digit) and tell you.

There’s the sensible answer. I always wanted to be a writer so I… nope, sorry, I’m bored with that already.

I’m afraid you’re going to have to suffer a more emotional yarn. It’s much more me. And of all things, it’s about a 110-year-old firearm.

When I was 12 years old, I saw my dad cry for the first and only time. When I asked him why, he told me something I didn’t understand.

“Every time an old person dies, a library burns down.”

The old person Dad was talking about was his friend, Percy. He took my father under his wing when my grandfather died and taught him everything from how to poach rabbits and pheasants to feed his family, to the song and flight pattern of every British bird. He also equipped him with the Latin names of wildflowers and a mine of other information that would stay with Dad forever.

Percy gave Dad his old shotgun: a Stevens Model 520 built in 1909. Percy fought in both World Wars, and the Stevens had been his “trench gun”. Designed by the genius gunsmith John Browning, the Model 520 was built in its thousands over the years, serving both the American and the British Army. Production only ceased in 1958, such was the weapon’s design and engineering brilliance.

Percy gave Dad his old shotgun: a Stevens Model 520 built in 1909. Percy fought in both World Wars, and the Stevens had been his “trench gun”. Designed by the genius gunsmith John Browning, the Model 520 was built in its thousands over the years, serving both the American and the British Army. Production only ceased in 1958, such was the weapon’s design and engineering brilliance.

Lordy it was a fearsome thing: a six-shot pump-action 12-gauge that could be “slam fired” (if you held the trigger and worked the slide, it fired automatically with every lock and load) and had a massive bayonet attached. It had saved Percy’s life, many, many times. It contained a world of stories that I would imagine as dad field stripped and cleaned it with me sitting watching and learning.

After Percy died, Dad never shot the gun again. Or indeed hunted. He still cleaned it religiously, and I grew to understand that the reason he did so was to spend some time with both his thoughts and Percy.

One day, while my newly pregnant wife was out shopping, he turned up at mine and gave me the gun. He told me I might need it to feed my family one day. We both knew I couldn’t kill anything, so it wasn’t difficult to know the real reason he wanted me to have it. Dad was dying, and it was his way of giving me something I could use to spend time with him when he was gone.

I had thought that the unlicensed, unregistered, gun couldn’t be any more illegal, but I stood corrected. Dad had obviously decided the bayonet was a bit dangerous with a grandchild on the way. So he’d simply hacked the front off the barrel to get rid. Now it wasn’t just an illegal shotgun, but an illegal “sawn-off” shotgun…

| ...the day came when I realised I didn’t just want to preserve my library for generations to come, but much more importantly to me, Dad’s. And Percy’s. |

I’ll never forget the conversation with my wife when she came in to find me frantically stripping out the gun’s guts after Dad left.

“What on earth has your dad given you there?” she asked.

“About five to 10 years depending on the judge, unless I render the bloody thing unusable in any way, shape or form…’ I replied.

Time passed. Dad’s library burnt down, and this time, I understood completely. And now it’s me that, 20 years after Dad’s death, still strips and cleans a long-since deactivated and unused gun that is well over a century old.

Now it’s me that spends a little time with a dead old man, as he explains how the bolt carrier sits correctly on the sled, or how the trigger sear is adjusted, or how important it is that the ejector is balanced and free.

So anyway, the day came when I realised I didn’t just want to preserve my library for generations to come, but much more importantly to me, Dad’s. And Percy’s. And anybody else long since passed. But I knew that if I did it, I owed it to them to do it properly and responsibly. I am, after all, all that is left of their voices.

So I went to university and learned how to write for a living. And I got my degree. Rightly or wrongly, where it takes me is of little concern. What really matters is that it helps me to tell the stories of people I loved who are no longer here.

That’s why I became a writer. For Dad’s sake.

And because of Percy’s gun.

Paul’s essay, “No Lay, No Pay” appears in “Common People: an anthology of working-class writers”, edited by Kit de Waal and available now.

Published: 13 May 2020

© 2020 Just Recruitment Group Ltd

If you enjoyed this article, you may like: Are you too old to make a career change? Hint: the answer is no!

You may also enjoy: “When we lose we learn”